'Skin I Live In' peels perverse layers of sex, obsession and revenge

Snakes have had a bad rap ever since the Book of Genesis hit the stands. Do one bad thing, and suddenly you're the eternal embodiment of evil, with the creepy ability to shed and replace your skin. When Flesh and the Devil are so intertwined, in and out of the Garden of Eden, that's a highly useful skill. Humans don't come by it naturally. They need the help of a very good plastic surgeon -- or a very malevolent one.

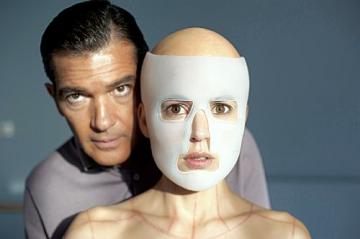

The eminent physician in Pedro Almodóvar's "The Skin I Live In" is Dr. Robert Ledgard (Antonio Banderas), whose late wife was horribly disfigured in a fiery car accident. Ever since, he has obsessively devoted himself to synthesizing a new kind of skin with which her life might have been saved.

Noble enough goal, huh? Using animal cells, he has finally cultivated in his lab dish a "perfect skin" that can withstand burns, cuts or any other kind of damage -- it even repels mosquitoes -- and (mirabile dictu!) is also highly sensitive to erotic caress. All he needs now is the right human guinea pig.

Bioethics, of course, strictly forbid such transgenesis, and as Dr. Ledgard gets closer to perfecting it, his peers grow increasingly skeptical of his methods and suspicious of the link between his tragic past and his star patient of the present.

That would be beautiful Vera (Elena Anaya), whom we first glimpse through a barred window in Robert's idyllic, isolated mansion -- an inaccessible prison protected by high stone walls and gates. She is doing a series of complex yoga exercises, totally covered by a flesh-colored body stocking that clings to her like -- well, like a second skin.

Down below in the kitchen, Robert's faithful housekeeper-accomplice Marilia (Marisa Paredes) sends up meals in a dumbwaiter that opens directly into Vera's locked room. Captive Vera and jailer Marilia seem to have a peaceful relationship. In years of enforced reclusion, Vera has lost many things but not her identity (Almodóvar's main sub-theme). She has learned to live in her new skin -- and to wait, pacing like a caged tiger, so as not to miss a chance of escape.

Exactly who is Vera, and why did Robert select her for his ultimate experiment? Therein lie the twisted details of a perverse tale involving violent death, mayhem, kidnapping, multiple rapes (as painful to view as in "Clockwork Orange"), several defenestrations, mad-scientist vaginoplasty operations, and "the intoxicating smell of burning flesh" -- for starters.

The subject matter, shall we say, is not quite mainstream fare. The techniques are quintessentially Almodovarian: backward and forward jumps in time sequence, deviant sexuality as motivational device -- sex everywhere, stoners on pills, kidnap victims learning to love-hate their captors with the noise, rather than the silence, of the lambs.

Almodóvar is the Luis Buñuel of our time. This quasi-Hitchcockian film does not live up to the soulful impact of his greatest ones ("All About My Mother," "Talk to Her," "Bad Education," "Volver") or to Fritz Lang's noir-horror pix or Georges Franju's "Eyes Without a Face" (1960) that inspired it. But the screenplay (by Almodóvar, in collaboration with his brother Agustin, based on Thierry Jonquet's novel) is diabolically fascinating. Composer Alberto Iglesias' music is terrific, and cinematographer José Luis Alcaine's camera work renders all the requisite darkness of the occasion.

As for the brilliant acting ensemble, Mr. Banderas' reptilian doctor is chilling. Ms. Anaya's Vera is matched only by her male alter-ego and alter-skin Jan Cornet. Marisa Paredes as materfamilias Marilia is a horrible hoot: "Their fathers were very different, but they were both born insane," she says of Robert and his maniacally oversexed brother. "It's my fault."

She's right, as the grand-Guignol finale proves.

Skin (come to find out) is actually an organ. Who knew? And who knew such organic material could stretch out into such a diabolically disturbing story of twisted love and revenge?