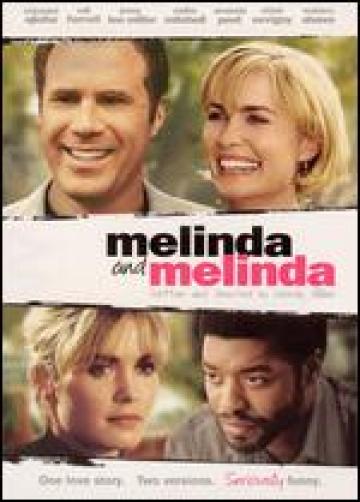

'Melinda and Melinda'

Woody Allen is the most screaming heterosexual in America.

Privately and professionally, only women need apply -- men don't interest him. Scenario: He rings Radha Mitchell out of the blue, says he thinks she's terrific (which he honestly does), offers her the lead in his new movie. Radha, stunned and flattered, never worked with him before, always wanted to, takes two full seconds to think about it. The title of Darryl Zanuck's autobiography -- "Don't Say Yes Until I Finish Talking" -- probably pops into Woody's mind. Keaton and Farrow pop into mine. It's a surefire way to pick up chicks and leading ladies -- two beautiful birds with one stone.

This is admiration (and jealousy), not disapproval. But I have even higher admiration for "Melinda and Melinda," which is among Allen's funniest entries of this fresh millennium, harking back to films of the previous one with a double variation on his favorite theme: the fickle fingers of infidelity, jealousy and romance.

The basic bright idea here is two parallel stories -- one comic, one tragic -- that straddle the fine line between those Greek masks. The two treatments are juxtaposed and sometimes overlapping but essentially unrelated, except for the dual enigmatic presence of Melinda (Mitchell).

In Allen's battle of the sexes, the smart Manhattan dinner or cocktail party is your main battlefield -- your conversational Bull Run -- and you show up with all the offensive intellectual and defensive emotional weapons you can muster. Laurel (Chloe Sevigny) and her actor-husband Lee (Jonny Lee Miller), for instance, seem particularly tense tonight.

They get a lot tenser when Melinda crashes the party in a wild-eyed state. She was married, had an affair with an Italian, lost custody of her kids, got stuck in a mental hospital, made a suicide attempt (it wasn't "a cry for help") ... That's just for starters. Melinda is, shall we say, a little fragile and self-absorbed -- just like the "Mme. Bovary" her creator-director so adores. "Let's face it," somebody says behind her back, "she's one of those people who'll always need help."

Things brighten up for her when she meets Ellis Moonsong (Chiwetel Ejiofor of "Amistad" and "Dirty Pretty Things" fame), who is writing a forthcoming opera for Santa Fe and wants to be the next Puccini. He is gifted, sensitive and unfazed by Melinda's confession of a certain murder. They're a perfect couple -- until Laurel falls in love with Ellis, too.

Meanwhile, behind story-door No. 2, high-powered director Susan (Amanda Peet) says her new film, "The Castration Sonata," is going to "put male sexuality in perspective." Her actor-husband (played by Will Ferrell), known for his brilliant interpretation of "Pygmalion" (he played Henry Higgins, as well as Lear, with a limp), is hugely smitten by Melinda and violently jealous of her attraction to everybody but himself.

These are not real people, of course, but neither are they stereotypes. They're literary/theatrical characters, moved like chess pieces by Allen and wonderfully performed by all. Aussie-born Mitchell (so fine as Johnny Depp's alienated wife in "Finding Neverland") is the only one who crosses the invisible comic-tragic line to shine in both stories. Sevigny's Laurel is the latest in a series of seriously excellent performances (she was Oscar-nominated for "Boys Don't Cry"), while Ferrell of "Saturday Night Live" takes the Allen signature lines and runs with them, as well as the shtick. Ferrell turns in an amazing, very funny homage-like imitation of Allen's trademark nebbish and stammering delivery. After a hot encounter with a "Playmate of the Month" nude conservative: "I'll never vote against school prayer again."

I can't help it. I'm a sucker for this salty repartee pretentiously peppered with highbrow mood music throughout -- a little Bach "Well-tempered Klavier" here, a little Bartok Quartet No. 4 there -- and for Vilmos Zsigmond's evocative photography, and most of all, for production designer Santo Loquasto's East Side apartment sets (this is his 24th Woody Allen film), glowing with rich, warm, autumnal golds and browns.

"Life has a malicious way of dealing with great potential," we are told. It might be said of Woody, except that, with a dozen masterpieces among his 40 (and still counting) films, nobody can honestly say this prolific icon's potential hasn't been fulfilled. Critics and moralists nevertheless love to take out their objections to his personal life on his films, which -- ironically -- are just what the neo-con culture doctors order: gentle PG-13 entertainments totally devoid of sex or violence.

"Comedy is tragedy that happens to other people," we are told by British feminist Angela Carter. "Melinda and Melinda" lets Woody Allen have and lets us eat his cake -- more of a cupcake, actually. Not much nutritional value, but it goes down and goes by deliciously fast.