'Dangerous Method' analyzes the twisted psychoanalytic trio of Freud, Jung and Spielrein

John Huston's "Freud," with Montgomery Clift in the title role, was underrated by the critics and under-respected by the college freshmen with whom I saw it in the mid-1960s. During the scene where Monty gives Susannah York a sexy new negligee, one wise guy shouted out, "Hey, it's a Freudian slip!"

Then and now, it's hard to resist irreverence when the ponderously serious subject is psychoanalysis and, in the case at hand, the intense relationships and conflicts among those who gave birth to it at the turn of the 20th century. But we will try to refrain from further freshmanic or even sophomoric cheap shots at senior figure Sigmund and his junior colleague Carl Jung in "A Dangerous Method."

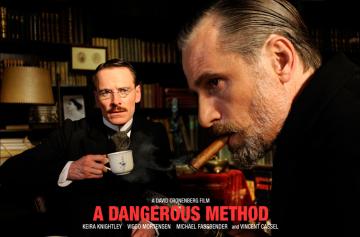

Director David Cronenberg's absorbing take on them is based on Christopher Hampton's play "The Talking Cure" (based in turn on John Kerr's book), in which the careers of Freud (Viggo Mortensen) and Jung (Michael Fassbender) intersect and coalesce around a tempestuous patient named Sabina Spielrein (Keira Knightley).

We meet her as she is dragged into Jung's asylum, screaming and writhing, face contorted and speech distorted -- in hysterical schizophrenic condition. Under Jung's patient questioning, the story emerges: She was much abused by her father. "Whenever he hit us, we always had to kiss his hand." How did she feel when he beat her? "It excited me." She eroticized the humiliation, self-loathing and incest. What's her interest now? "Suicide and interplanetary travel." Bottom line: "I must never be let out of here."

But Sabina, once she's calmed down, also confesses an interest in Jung's research. "Do you think there's any possibility I could become a psychiatrist?" she asks. "Yes," comes the answer, "you have the main quality -- insanity."

Jung is a busy man with his wealthy wife and growing family and pioneering dream-interpretation and word-association work. He could use a little help, not just from Sabina but from Freud himself. They first meet in Vienna in 1906 -- for a wonderful dinner scene that establishes their collaboration.

Eventually, though, Jung comes to see that "obedience is more important than originality" to the imperious Freud, and a conflict -- and later rivalry -- develops between them over their differing concepts of sex, religion and the unconscious. Jung views Freud's theories as incomplete and too exclusively concerned with repressed emotions and desires. He proposes the existence of a deeper "collective unconscious" in which sexuality is more of a sublimated spirituality, rather than the other way around.

Complicating the personal and professional issues is Dr. Otto Gross (Vincent Cassel), a brilliant but debauched and drug-addicted colleague who is sent to Jung for treatment. (You get all the tough cases when you're tops in your field.) "Never repress anything," Gross decrees. "I think Freud's obsession with sex has to do with the fact that he doesn't get any."

Jung is likewise restless. Gross advises him to sleep with Sabina. Wouldn't that be unprofessional? Occupational hazard, Gross shrugs. It will be the first but not last time that Jung's therapeutic and erotic objectives converge. And it puts a serious strain on the relationship with Freud, who considers him an adopted son as well as a useful Swiss-Protestant ally in a field dominated by Viennese Jews -- "the goy wonder" of future of analytic psychology.

As in "Eastern Promises," "A History of Violence" and "Crash," Mr. Cronenberg interweaves theory with narrative and with his characters' inner lives in a literate and sometimes darkly funny way. Mr. Fassbender is fine as the straight-laced Jung; so is Mr. Mortensen's cigar-chomping Freud. They're both low-key almost to the point of dull, actually.

Ms. Knightley, by contrast, chews up the psychoanalytic couch and scenery with her jutting chin, her shaking and quaking, and her overall over-the-top portrayal. "Don't you think we ought to stop?" Jung ventures weakly at one point. "I want you to be ferocious! I want you to punish me!" is her answer. When things inevitably descend into the standard melodramatic elements of infidelity and guilt, it's not really her fault.

What Sabina wants more than anything is "to give people back their freedom." What Jung wants, finally, is to explore the idea that full sexuality demands destruction of the ego, a kind of self-annihilation -- the opposite of Freud's idea: "We have to go into uncharted territory."

That's all-sexual terrain, though there's more smoke than fire in it here. "A Dangerous Method" is fascinating, but when you learn too much about the real human beings behind the myths, they all somehow seem to -- well, shrink.