"Biutiful" looks at one man's flawed but beautiful life

"To make God laugh, tell him your plans." -- Mexican proverb

Everything about "Biutiful" -- starting with its title -- is unnerving and idiosyncratic, as are all of virtuoso director Alejandro Gonzalez Inarritu's tragic visions. His vision here concerns nothing less than a doomed man's struggle to reconcile fatherhood, love, crime, guilt, death and the afterlife.

A rather jam-packed agenda.

Mr. Inarritu's equally ambitious "Amores Perros" (2000) and "Babel" (2006) were sweeping, multi-storied affairs. "Biutiful," only his fourth feature, is a single linear tale, set in the sordid underworld of Barcelona, where life is anything but beautiful -- no matter how you spell it. And also unlike his previous films, this one is elevated by a single riveting performance by one of the greatest actors of our time.

It begins (and ends) in a silent snowy forest, with a cryptic Bergmanesque meeting and conversation between two young men. One of them is Uxbal (Javier Bardem), a scruffy man with a scruffy ponytail and very scruffy life. His diversified business of drug-dealing, DVD piracy and other black market operations requires real people skills: Adept at bribing the police, these days Uxbal is trafficking most profitably in illegal Chinese construction workers.

He has spiritual skills, as well: Grieving parents pay him to contact the restless souls of their dead children. In one eerie scene reminiscent of "Cries and Whispers," he communes with three boys in parallel coffins while the ghost of a fourth watches from a chair. "Why can't you leave?" he asks them softly. "What is keeping you here?"

As a psychic, Uxbal may or may not be a charlatan. At times he does seem to have telepathic powers -- for better or, usually, worse -- but no great gifts of divination for himself. Chronic painful physical symptoms finally drive him to a doctor, who delivers the ominous words: "You should've come in sooner." He has a couple of months, at best.

It's bad news for his business and even worse news for his domestic non-tranquility. Single dad Uxbal is indulgent of daughter Ana (Hanaa Bouchaib) but painfully tough on son Matteo (Guillermo Estrella). Their bipolar mom, Marambra (Maricel Alvarez), a booze-and-pill-addicted "masseuse," complicates things with her noisy efforts to get back in their good graces.

Uxbal, in his terrible way, is a terribly good father, constantly checking on his kids and taking care of the sweet Chinese babysitter who takes care of them during the day. But his concern for Barcelona's marginal, modern-day slaves -- Chinese, Senegalese, Gypsy, Indonesian sweatshop workers -- will have ironically fatal results.

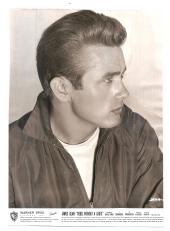

Superlatives are insufficient for Mr. Bardem, so brilliant in Alejandro Amenabar's "The Sea Inside" (2004), Woody Allen's "Vicky Cristina Barcelona" (2008) and Oscar-winner for his villainous role in the Coen brothers' "No Country for Old Men" (2007). His intense tour de force here -- the first all-Spanish performance nominated for an Oscar -- lies in his sorrowful face, reflecting the world's and his own moral failings.

Ms. Alvarez is a match for him with her own unfathomably sad eyes, vulnerable and dangerous, smoking and blathering, hopeless and helpless.

Mr. Inarritu's script, based on his own original story, employs a kind of dark obverse of Magic Realism. He uses surreal devices only sparingly, but stunningly, with jarring images of Uxbal's Inferno -- our hero's last hurrah in a strip club drug den, featuring naked dancers with nipples on their buttocks.

(Don't ask ... or tell.)

Gustavo Santaolalla's powerful, percussive score is complemented by the adagio from Ravel's Piano Concerto in G, a wrenchingly gorgeous piece that Mr. Inarritu says inspired his whole film, which is relentlessly downbeat and rough viewing, all 148 minutes of it -- even rougher than "Amores Perros," where random lives collide in a gruesome car crash, or "Babel," where a single gunshot shatters Brad Pitt's and Cate Blanchett's lives, plus three other families, as well.

Mr. Inarritu is a tripodal force in a truly tremendous Mexican New Wave -- the other legs being Guillermo Del Toro ("Pan's Labyrinth") and Alfonso Cuaron ("Children of Men"). Some critics complain about his "miserabilist humanism" or his "redemption jabber" or the fact that he leaves unresolved subplots, such as Uxbal's psychic side and the strange gay love affair of two Chinese sweatshop bosses in "Biutiful" -- whose dubious title comes from Ana asking, "How do you spell 'beautiful'?" and Uxbal's reply, "Like it sounds."

Tangential elements fascinate Mr. Inarritu as much as, or more than, plot-driving issues. What, exactly, is relevant and irrelevant in life's nonexistent "plot"?

More important questions: What do you do when your last days are numbered, and are you blessed or cursed to know the number? Do you devote yourself to the living or the dying? And where do you go when you die? Heaven or hell? Or just into the memory of others?

There's nothing very humorous about this requiem for a caretaker, except Mr. Bardem's observation -- in a subsequent interview, not the film -- that heaven sounds nice but dull: "If only you could get an apartment there and then go to hell for the weekends."