'Godard at 70': A biography for people in love with thinking

BY BARRY PARIS

BLOCK NEWS ALLIANCE

"Godard: A Portrait Of The Artist At Seventy." By Colin MacCabe. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. 456 pages.

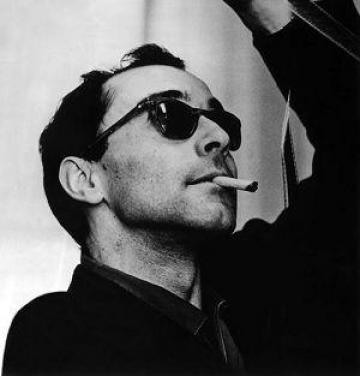

Sometimes you can judge a book by its cover: Jean-Luc Godard, a cigarette implanted between his lips, reaches out to direct us through the enlarged "O" of his surname, for three-dimensional effect. It's an elegant trompe-l'oeil design for an elegant biography by Colin MacCabe.

Godard once famously said that every film should have a beginning, a middle, and an end - but not necessarily in that order. Since leaving filmdom Breathless in his 1960 debut, his mastery of the medium is no less dazzling or baffling, while he himself continues to engage us.

So does this book, which is both scholarly and readable but, like Godard's films, makes serious demands on its audience. The story of Godard's life is intellectual and sociopolitical. Born into a prominent French-Swiss Protestant family, he belonged to both the Parisian elite and the Alpine bourgeoisie. He was a disaffected teenage thief and a less-than-stellar anthropology student at the Sorbonne, but his real education took place in Left Bank cinema clubs and the Cinematheque Francaise.

"American movies were my parents - my mother and father," he declared.

Godard was destined to become, first, a brilliant critic and leading light - with Truffaut, Rohmer, Chabrol - of the journal Cahiers du Cinema and then, in a quick leap from theory to practice, the Nouvelle Vague vanguard director. In 12 films between 1960-66, he "revolutionized the language of cinema," says MacCabe, with a dazzling range of innovations in sound, image and editing.

What he didn't invent, he refined: jump-cutting, for instance - the abrupt shift from one scene to another without fade or transition; slow-motion stop-action to lengthen a slap of the face, a turn of the head, a sudden dive across the breakfast table toward somebody's throat - images not necessarily of special "meaning" but of visceral impact. Images to savor rather than to signify.

So stunning, his devices.

So problematic, his films.

So what's the story? Of a Godard film, I mean. Don't ask. Generally there isn't one, just a series of moments. The "action," such as it may be, proceeds by montage instead of "plot."

I am crudely summarizing what MacCabe eloquently explicates. Especially good is his analysis of how Godard came to hate the Hollywood and America he earlier adored; how, in his view, the liberators of France became the oppressors of Vietnam.

Godard's intense radicalization came in 1968, the watershed year, MacCabe argues, of the 20th century's second half: the Viet Cong's Tet offensive, the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia, the assassinations of Martin Luther King, Jr., and Robert Kennedy, the ascendance of the Big Three - sex, drugs, rock 'n' roll - and violent anti-war protests worldwide.

Godard chose to take up with the French Maoists, and became enmeshed in the Byzantine vicissitudes of French Marxist politics, spending an enormous amount of his time, energy, and intellect trying to reconcile excellent theory with deplorable practice. MacCabe is forced - or forces himself - to do the same.

"It is difficult to find a Maoist in the 21st century," he acknowledges wryly, even as he rationalizes the French left's embrace of Mao's monstrous Cultural Revolution. Truly committed to the movement, Godard never recovered from the disillusionment of its collapse.

MacCabe is, by occupational hazard, an apologist for Godard, but his book is no whitewash. In chronicling such projects as "One Plus One" (the fascinating Rolling Stones film), MacCabe exposes Godard's obsessive need to kowtow to the young. Here also, in grim detail, are full accounts of his endless fussing and feuding with other New Wavers - of whom Godard's greatest love/hate was reserved for Francois Truffaut (and vice versa).

Evident on every page is MacCabe's profound knowledge of film and literary criticism. Not least of his virtues is a persuasive demonstration of how Godard & Co. defined and elevated an entertainment into an art form - America's own great native art that we were too dumb to recognize or preserve: Ninety percent of all silent films are destroyed. Those that remain were mostly saved by the French.

The book is not perfect. The editor lets MacCabe include the fabulously obscure Viktor Shklovsky, but also lets him misspell it twice. As a reader, far from resenting an author's vocabulary that makes me look up words, I enjoy doing so. But when three dictionaries - including a 10-pound unabridged - fail to reveal what "scortatory" means, I think maybe MacCabe should have found a synonym.

Those bits are nits. "Godard: A Portrait of the Artist at Seventy" is a major achievement: biography, history, criticism, philosophy, gloriously sweeping - like Godard's films, for people in love with thinking, not in a hurry for the ending.

[Reprised: April 30, 2012 from the Sept 18, 2004 original]