Obituary: Tony Curtis / Classy man underrated as an actor

June 3, 1925 - Sept. 29, 2010

The first time I met Tony Curtis in Los Angeles to discuss co-writinghis autobiography, I told him -- by way of clumsy introduction -- that at age 11, my best friend and I went to see his 1958 action film "The Vikings" three times in two days, adding, "We desperately wanted to BE Tony Curtis."

He nodded and replied: "So did I."

It was a typically wry, self-effacing, truthful thing to say. He was, after all, not really "Tony Curtis." He was Bernie Schwartz of the Bronx, born to Hungarian Jewish immigrants Manual and Helen on June 3, 1925.

He died Wednesday, at 85, of cardiac arrest at his home near Las Vegas. Being and becoming "Tony Curtis" would be a lifetime process that took him from the depths of poverty in the Depression to the heights of Hollywood stardom, and more fine performances than he was ever given credit for in some 120 films.

Mr. Curtis joined the Navy in 1943, serving in the South Pacific. After the war, he took acting classes at the Dramatic Workshop of the New School, where fellow students included Walter Matthau, Harry Belafonte and Bea Arthur. Spotted in an off- Broadway production, he was signed by a talent agent to a contract with Universal Pictures, who changed his name, taught him how to fence, and gave him the courage to approach starlets with the line, "I've been assigned by Universal to teach you how to kiss."

His pictures would generate bigger audiences and more money than all the "highbrow" actors combined. But he never won an Oscar. He was just too -- too what?

Too popular.

Mr. Curtis also was intensely emotional and great fun, as was my experience of working with him intimately for two years. Once at dinner in Manhattan, he introduced me to Bill Cosby with deadpan solemnity: "I never travel without my biographer -- in case I say something significant."

Another time, when I inquired about the young ages of the five women he married, his response was, "I'd never marry a woman old enough to be my wife."

The first of them was Janet Leigh, best known for her demise in the shower during Alfred Hitchcock's "Psycho" (1960). They became one of the Hollywood's most glamorous couples, parenting actress-daughters Jamie Lee and Kelly. His issues with subsequent wives Christine Kaufmann and Leslie Allen helped fill the pages of our book. Drug and alcohol addiction comprised other issues.

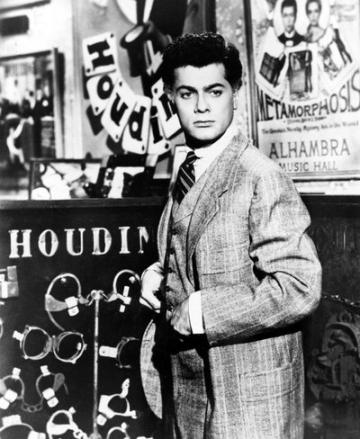

But the most -- and best -- of his issues were the movies, those marvelous pieces of action entertainment: "Houdini," "The Great Imposter," the silly "Son of Ali Baba" (in which his line "Yondah lies the castle of my faddah, da caliph!" was much mocked), "Trapeze" with Burt Lancaster, "Operation Petticoat" with Cary Grant, "Taras Bulba" with Yul Brynner, "The Great Race."

Everyone has his or her favorite Tony Curtis films. Mine was his brilliant, terrifying performance in "The Boston Strangler" (1968) as serial killer Albert DeSalvo. He was deeply upset when overlooked for an Oscar nomination for it.

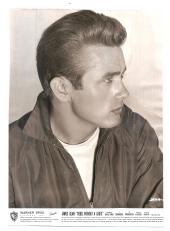

The rest of the world most remembers "Some Like It Hot," designated by the American Film Institute (and most public polls) as the "funniest American film of all-time." It's the 1959 classic in which two hapless musicians join an all-girls band to escape the Chicago Mob. Producer David O. Selznick told director Billy Wilder, "You want machine guns and dead bodies and drag gags in the same picture? Forget it, Billy. You'll never make it work."

With Marilyn Monroe singing and Mr. Curtis and Jack Lemmon in drag, it worked. Under Wilder's inspired direction, the stars gave the performances of their lives.

Curtis: "You play the market?"

Monroe: "No, the ukulele."

Marilyn got the raves, but the unsung hero of that film's success was Mr. Curtis, who played his drag "straight" (and does a brilliant Cary Grant imitation -- his own idea), while over-the-top Lemmon mugs and cavorts. But Lemmon got the Oscar nomination.

Mr. Curtis was never much recognized by Hollywood, in general. The Academy, in particular, never stopped thinking of him as a light-comedy leading man. But in fact, Mr. Curtis could and did do it all. Anyone who still doubts his abilities as a serious and versatile dramatic actor has never seen his amazing performances in "The Boston

Strangler" or "Sweet Smell of Success" (1957) with Burt Lancaster, a box-office failure now acknowledged as an American noir masterpiece. Mr. Curtis played Sidney Falco, a sleazy publicist in service to Lancaster's corrupt newspaper columnist, modeled on Walter Winchell.

Mr. Curtis -- in and out of the Rat Pack -- was also on the cutting edge of the Civil Rights movement. In 1958, he co-starred with Sidney Poitier in "The Defiant Ones," as the escaped convict-heroes of a powerful "message" film for which they both received Best Actor nominations. At Curtis' insistence, Mr. Poitier was given co-equal billing in the credits -- the first black actor so credited.

"That's how I got top billing for the first time in my life," Mr. Poitier told me. "I think that speaks a lot of Tony."

His personal and professional nadir came in 1984, when -- after a family intervention -- he entered the Betty Ford Center for substance abuse. Soon after, he was nobly and successfully recovering for the rest of his life. His last and happiest marriage, in 1998, was to "Sweet Jilly" -- Jill VandenBerg, the statuesque blonde who delighted him and made his life cozy in their scenic ranch home outside Vegas.

A lifelong artist, Mr. Curtis painted colorful Matisse-like acrylic canvases and assembled brilliant box constructions inspired by Joseph Cornell (whom he befriended and supported in the 1950s). He attributed his recovery in large part to the energy he put into his art.

You can tell a classy one from a boorish one by the way he treats his fans: One day on our book tour in Chicago, Mr. Curtis and I went for a walk down Michigan Avenue and halted at a big intersection, waiting for the traffic light to change. I pointed over to a huge chartered bus -- also stopped for the light -- in which dozens of excited tourists were jammed up against the windows, waving at him and mouthing his name.

Without a moment's hesitation, he went up to the door of the bus, the driver opened it, everybody cheered, Mr. Curtis stuck his head in and said: "Good afternoon! You must thank your tour guide for arranging this nice meeting for us."

Film historian and longtime Post-Gazette critic Barry Paris co- wrote "Tony Curtis: The Autobiography" (1993) for William Morrow & Co.